Introduction

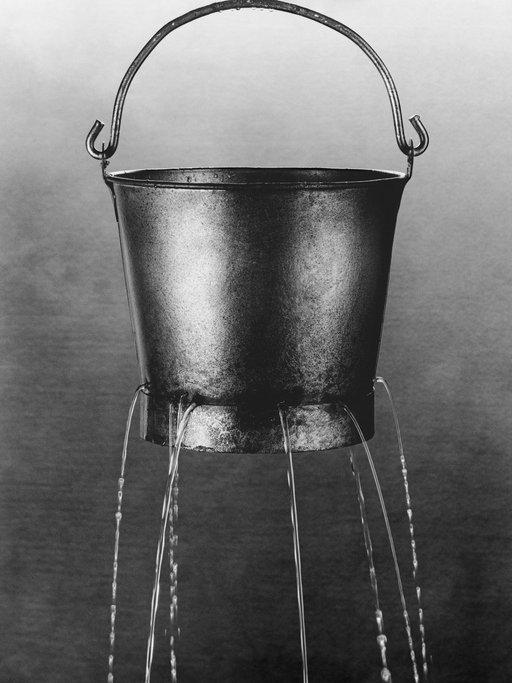

iStock: IPGGutenbergUKLtd

On September 5, 2024, a coalition of local and national environmental justice and clean water groups had the opportunity to meet with the White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB) to make the following two recommendations:

That serious holes in EPA’s proposed Lead and Copper Rule Improvements (LCRI) be closed, so that the final rule is maximally public health protective, science-based, and justice-centered; and

That the LCRI be enacted as soon as possible (and no later than October 16, the day when EPA’s problematic 2021 Lead and Copper Rule Revisions (LCRR) would go into effect and cause much confusion to water utilities, state oversight agencies, and the public alike).

Meeting highlights

With statements from Ronnie Levin, instructor at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health’s Department of Environmental Health, and Elin Betanzo, president and founder of Safe Water Engineering LLC, our coalition highlighted the significant financial benefits of a public health protective, science-based, and justice-centered LCRI. Research supporting our coalition’s position included the 2023 paper by Levin & Schwartz, titled “A better cost:benefit analysis yields better and fairer results: EPA's lead and copper rule revision” and the 2024 Safe Water Engineering report by Elin Warn Betanzo and Vanessa Speight, titled “Lead Service Line Replacement Costs and Strategies for Reducing Them.”

Reinforcing our coalition’s shared view that a strong LCRI is in the nation’s best interest, the Campaign for Lead Free Water argued for the necessity to fix grave flaws in the proposed regulation’s public education and lead service line (LSL) replacement requirements, so that the final rule:

reliably minimizes — rather than prolongs or exacerbates — public health risk, and

aligns with the Biden Administration’s highly publicized commitment to “protect children and communities across America from lead in drinking water.”

Under the 1991 Lead and Copper Rule (LCR), both the public education and the LSL replacement requirements are “treatment techniques” — this means that they must prevent “known or anticipated adverse effects on the health of persons to the extent feasible.” Yet, as proposed by EPA, these requirements will achieve far less than that. Specifically:

The public education requirement will leave the public a) misinformed about the ubiquity of lead in water in the vast majority of buildings and the vast majority of taps, and b) unequipped to adopt best practices for significantly reducing — if not altogether preventing — routine lead-in-water exposures; and

The LSL replacement requirement will allow water utilities to a) leave in the ground — at least short-term and in some cases possibly long-term — short lead “connectors” (which are essentially short LSLs), and b) replace only the portion of a LSL from the water main to a home’s exterior wall, while leaving the portion of the LSL inside the home intact. This practice risks resulting in millions of “partial” LSL replacements which, under certain circumstances, can place people at increased risk of lead-in-water exposures, in the short- and long-term. Precisely due to this danger, in March 2011, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) called for an “immediate moratorium” on these replacements, emphasizing that:

Research by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention scientists published this month based on 63,854 children from Washington, DC, demonstrated that the risk of an elevated blood lead level for a child is not diminished by living in a home with a partially-replaced lead service line compared a child living in a home with an intact lead service line, and that it is more likely that the partial replacement increases the risk of an elevated blood lead level about 40%. Thus, there is no benefit and there likely is harm from this activity that costs thousands of dollars per home.

We wrote about these problems extensively in our February 5, 2024 public comment to EPA.

We made our statement to OMB with the knowledge that, if it chooses, this office has the authority to return a proposed rule to EPA for further consideration and revisions. Our brief statement is below.

Background

For those unfamiliar with OMB, it is an office within the Executive Branch charged with, among other things, cost-benefit review of “significant” Federal regulations proposed by government agencies. OMB gained this authority—which Georgetown Law Professor Lisa Heinzerling characterizes as a “power grab”—from executive orders issued by Presidents Clinton and Obama. In 2016, Heinzerling stated that:

Few environmental statutes in this country put the President (or his aides in the White House) in charge of environmental decisions; most give the job to the EPA or, more specifically, its Administrator. Even fewer environmental statutes require rules to be evaluated according to cost-benefit analysis; most specify a different kind of decision-making framework for such rules.

Nevertheless, the Obama administration has continued and deepened a longstanding practice of White House control over EPA rules, with cost-benefit analysis as the guiding framework. OMB is the central player in this structure: it reviews, under a cost-benefit rubric, all agency rules that it deems “major” under executive orders mandating this review. EPA rules deemed major by OMB are not issued without OMB’s imprimatur. Thus does the OMB director become the EPA Administrator’s boss.

In 2013, Heinzerling offered this important history about the OMB:

In 1994, eyeing the first Republican takeover of the House of Representatives in forty years, Newt Gingrich proposed an aggressive series of legislative reforms, bundled together as the “Contract With America.” Among the most contentious of the proposals was the “supermandate”: a requirement that all rules protecting human health, safety, or the environment pass a cost-benefit test. Critics of what President Bill Clinton dubbed the “Contract On America” feared that applying a cost-benefit test to health, safety, and environmental rules would often spell their doom, as these rules produce benefits — in human health, in longer life, in cleaner air and water and land — that are hard to quantify and even harder to monetize. President Clinton vetoed bills to fund the government in part because they contained the supermandate, leading to the government shutdowns of 1995 and likely contributing to Clinton’s political renewal.

Thanks to Sunstein [Harvard legal scholar who, under President Obama, served as the Administrator of the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) within the OMB], though, the supermandate is back. By pressing agencies to adopt cost-benefit analysis as a decision-making framework wherever the law allows it, Sunstein’s OIRA has, by executive fiat rather than legislative enactment, imposed a cost-benefit supermandate wherever the law is ambiguous (which it often is). Newt Gingrich might be pleased, but those concerned with health, safety, and environmental protection should not be.

OMB is an office known for its lack of transparency (indeed, during our coalition’s 30-minute call, OMB staff stayed silent). It has also been criticized for its lack of accountability (of course, lack of transparency and lack of accountability tend to go hand-in-hand).

Still, we hope that the OMB heard us and that they will take the necessary steps to ensure that EPA’s proposed LCRI is both strengthened and issued very soon.

campaign for lead free water oral statement

Thank you, OMB, for this opportunity.

We’d like to bring to your attention two grave weaknesses in the proposed Lead and Copper Rule Improvements (LCRI) that, if not addressed, will prolong and even increase health risk, ensuring health harm for generations to come. They involve public education and lead service line (LSL) replacement.

Public education

First, the public education requirement continues to leave communities in the dark about what the proposed LCRI makes clear—namely, that taps can and do dispense lead, even when:

water systems meet LCR requirements, and

LSLs are absent.

To function as an integral “treatment technique,” as laid out in the LCR, public messaging must finally give consumers complete, accurate, and scientifically sound information about the benefits of available precautionary measures that can dramatically reduce, if not eliminate, routine exposures. We’ve shared with you a letter we sent to EPA that delves into this matter in detail and spells out concrete recommendations for corrective messaging. It’s urgent that people are given the tools to protect themselves from both chronic and acute exposures that the rule’s other three “treatment techniques” – source water treatment, corrosion control treatment, and LSL replacement – cannot address.

Lead service line replacement

The second weakness is the proposed definition of a LSL, which covers the portion of pipe from the water main to the “building inlet” (proposed LCRI, p85054). As EPA has acknowledged in writing, the term “building inlet” is open to interpretation and might result in partial pipe replacements that leave in place the portion of the line inside people’s homes. As DC has taught us, this is a dangerous proposition that can result in large-scale lead poisoning.

The definition also excludes lead connectors under two feet, which are short LSLs.

For the LCRI to become a full LSL replacement rule, this definition must include the portion of the line inside people’s homes as well as all lead connectors [regardless of length]. If this correction isn’t made, millions of households are likely to be placed at prolonged and even increased risk of exposure to LSL lead, long after their utility declares all LSLs fully removed. The environmental justice concerns this would raise are very serious, especially for those communities forced to pay for these replacements.

In closing, the proposed LCRI undermines the benefits of the investment of billions of public and ratepayer dollars.

OMB must charge EPA to correct these fatal flaws.

Thank you,

Yanna Lambrinidou, PhD

Paul Schwartz